As I write this post, thousands of others, both bot and human, are also typing happily away, helping create the glut of content that will hit the internet in the next seconds, minutes, hours and days.

As of 2016, sites within the WordPress network — those hosted on WordPress.com or that have the Jetpack plugin installed — published an average of 24 blog posts per second. While WordPress is extremely popular, powering roughly one-third of all websites worldwide, sites within its network still represent only a fraction of the internet.

Some of this content is genuinely helpful or newsworthy. Some articles will become recognized as groundbreaking pieces of journalism, others as evergreen, go-to pieces for constructive advice.

The vast majority will never be seen and never be shared — some unfairly and some very deservedly so. How do you know what to trust within the profusion of SEO and marketing advice published every day?

1. Look at the data.

First, see if the article you are reading cites any data at all. If not, does it contain actionable items, or merely vague advice?

Credible sources will often cite third-party studies or produce case studies of their own. If no relevant studies are available, a good source will offer examples or actionable steps appropriate to the content. These sources have taken time to research the topic or and think more deeply about the advice being offered.

Data can lie

Data can tell many stories based upon the perspective of the individual performing the analysis.

If an article presents a study, dig into the methodology. Are the sample sizes too small? Is the industry being surveyed relevant to your firm? Are the authors drawing conclusions that do not necessarily follow from the data? Did the person publishing the story do the work, or is it someone else's work republished? (There's nothing wrong with citing studies, but the citation should be obvious.)

For example, let's say that Custom Legal Marketing has prepared a link building study. We built five links and one long-form page for five law firms. Our data show that four of the five websites jumped two places in search results for their target keywords.

Can we justifiably say that 80 percent of all firms will benefit from five links and one new page? No. The data sample is far too small. There is no mention of the time period for the search results changes. The study also fails to take into account other factors that may have influenced the movement. And it suggests that there is a one-size-fits all solution to SEO. We may be able to write a catchy headline, but we cannot claim to be providing good advice.

Case studies are anecdotal

A case study can offer instructive insight into the way an author or organization thinks. However, a case study is by definition the result of one person's experience with one sample. The same methodology may not produce the same results for other websites or web pages. If an author claims universal promises based on one sample, be wary.

2. Find the date.

While an older publish date does not necessarily make an article irrelevant, the fields of marketing and SEO change so rapidly that articles covering these topics are more likely to become obsolete quickly.

All articles should show a publish date. If the article has been updated and republished, it should indicate when it was updated. Outlets that hide the publish date may knowingly be providing outdated advice disguised as a new post.

3. Read the article.

This seems obvious, but really, read the article. Read it all the way through. Does the conclusion match the headline and introduction? Are there conflicting facts within the body?

Many articles get shared based only on a clickbait headline. A 2016 study performed by Columbia University and the French National Institute found that 59 percent of links shared on social media were never clicked.

Yes. Over half of all people who share links do not click on them. Even if an article found its way to your reading list by way of a trusted source, there is no guarantee the person who shared it actually read it.

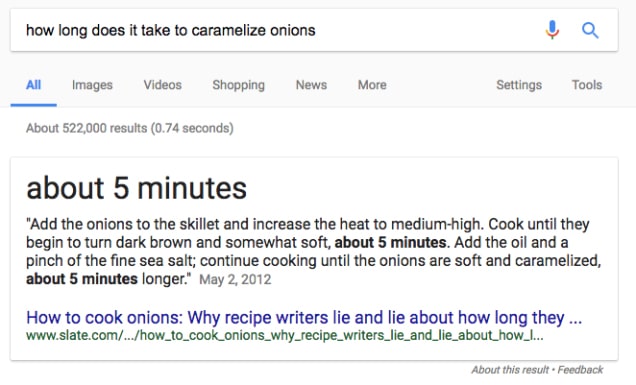

The case of the caramelized onion

As an example, take the controversy over Google's advice about caramelizing onions. Caramelizing onions takes a long time — at least 30 minutes and maybe over an hour if done correctly. However, many recipes claim you can accomplish the task in 5 to 10 minutes. This can be frustrating.

Tom Scocca, angered by all the incorrect advice putting home chefs around the world behind in their cooking schedules, wrote a piece that countered the false claims and gave correct cooking times based on the level of heat. It was published in Slate, and it received a lot of readership. The New York Times changed its official recommendation for caramelized onion cooking times. Scocca himself says it “might be the most valuable journalistic work I’ve ever done.”

All this notoriety got the attention of Google's algorithm, which began citing the article in a featured snippet that provided the answer to the query, “how long does it take to caramelize onions?” Only the snippet Google's algorithm has chosen is wrong (5 minutes) — the algorithm is pulling content from the "bad advice" section of the article. The result is contrary to the whole point of the article.

Crowdsourced answers are not always correct or complete. Do your own due diligence and read.

4. Be wary of promises.

There are no universal answers to marketing and SEO questions. There are time-proven tactics in each field, like link building and email marketing, that will work for many. But there is no single, comprehensive strategy that will work for all firms. People who claim otherwise are selling you promises they cannot keep.

Does the author ask you to make magical assumptions that SEO (or any other tactic) will be the answer to all of our problems? Does it suggest you can focus all your efforts on one thing? Does it guarantee results for specific actions? Be suspicious of any author who claims to have all the answers.

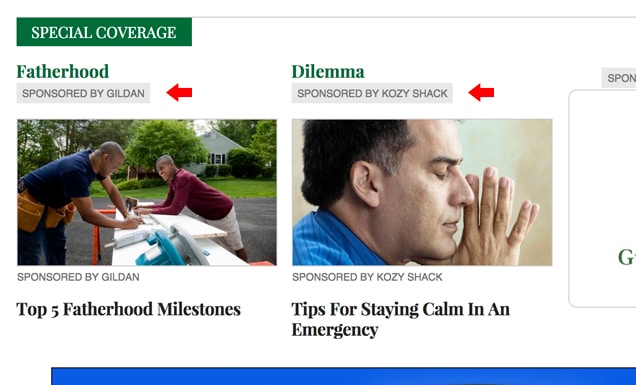

5. Look for sponsorship.

The Onion, which specializes in fake news as satire, is particularly good at identifying sponsored content. The Onion, perhaps ironically, has a reputation as a fake news source to maintain. It needs you to know which articles are fake, and which are only maybe fake.

Sponsorship of an article or study does amount to inaccuracy. However, sponsorship can indicate a propensity for a pre-determined outcome. Do a little research into the author or company the author represents. Does either have a vested interest in pushing a specific narrative?

6. Look for supporting evidence.

A lot of advice sounds good either because it is offered repeatedly, and therefore seems correct through familiarity, or because it provides solutions that seem relatively easy to implement. In fairness, some marketing and SEO tactics are simple. Others are complicated. All are part of a constantly shifting plan unique to your firm.

When you read through an article, pay attention to its thoroughness. Has the author done her homework? If an article offers advice you think is too good to be true, Google it. Do not just trust one source.

7. Consider whether the advice is relevant to your industry.

The legal industry, like any other, faces distinct marketing and SEO challenges. State bars set rules and guidelines for what firms can and cannot do. Attorneys handle sensitive information and have to carefully consider the ethics of any content they produce. People who need legal services are not likely to make an impulse decision — an action many retail companies rely on.

For example, a recent email that found its way into my inbox contained a link titled: “Inbound Marketing: 450% average ROI from Facebook advertising and organic content effort.” Wow, 450 percent! Pretty incredible.

Though the title is pure clickbait, the case study mentioned is actually very thorough, detailing an effecting marketing campaign that combined social media posts with relevant organic content. It offers some good advice.

However, the client involved in the study is a shoe company. People who are purchasing shoes have a whole different set of considerations than those looking for a lawyer (or for a marketing company).

Do you get a lot of leads from Facebook? If you do, great! This article might be helpful. If you are a law firm, however, you likely do not. Is it safe to assume that users will change their behavior drastically enough to give you that kind of return on investment? Again, likely not. An article may be presenting good advice, it just may not be good for you.

8. Read the comments.

Large sites like Moz, Ahrefs or even Google's own blog allow comments and have enough of an audience that their articles receive responses. Admittedly, comment threads are not always a hotbed of critical thinking. You may have to skim through some obvious spam.

However, if an author has written an article that resonates with readers, or one that is contrary to their own understanding of a topic, readers are likely to share their thoughts. You may find a comment string in which several people offer evidence that either furthers or disputes the conclusion of the article. These additional sources can be helpful in evaluating the overall quality of the original piece.

Above all, think critically when reading any advice. Dig into data and look at its source. Ask questions. And always remember that popularity does not imply accuracy.